Skilled management and effective teamwork are as vital

in the construction industry as anywhere, yet very little knowledge exists

of what ingredients make a successful team. Peter Lansley has developed

Arousal, a computer simulation of management decision making, and used

it to find out what makes a good team tick.

The University of Reading Department

of Construction Management has used the system as the basis of its study

of understanding and improving management performance. The study consists

of consultations with companies and a series of workshops in which company

managers work together to recreate the working environment.

Using the Arousal package with small teams of managers, it

is possible to uncover and light those factors which are to complex to

study in everyday work.

Written by Peter Lansley, Arousal is run on an IBM PC with

256 K memory. Despite the modest computing power the program is a powerful

one, using inference mechanisms not unlike those employed in the latest

knowledge-based systems.

Responsive

Used in the simulations, the model in effect "becomes" the company:

it responds to the decisions of the panel in the same way that a real company

would respond to managerial decisions in the light of the prevailing market.

In turn this modifies the behaviour of the panel in its next round of decision

making.

A major benefit of the program is its extreme flexibility.

As well as being used in the Reading research programme, Arousal is also

used for training schemes, and has been used to provide specific models

of major UK and US firms. These models can help the companies gain a better

insight into their own workings and to help improve efficiency.

One of the main findings reinforces those from earlier research

- teams which comprise individuals from different backgrounds invariably

perform better than those with similar experience. The present business

environment will not support firms which cannot balance, for example, engineering

solutions to business problems with financial restraints.

However, the most intriguing findings come from comparisons

of performances achieved by teams which have been constructed so that each

has a broad and balanced range of experience and background among its members.

Even so, it might be expected that there would be substantial

variations between the performances of small teams and this is the case.

These differences can be largely related to the degree of fit between the

reasoning processes of individual team members.

Problem solving

In some cases individual team members have been found to have compatible

reasoning processes. They look at the world, learn about it and solve problems

in similar ways.

Because their members speak the same language and think the

same way, they can make fairly rapid progress. These teams are characterised

by harmonious working and mutual respect.

However, compatibility has some drawbacks, not least when

an unexpected or unfamiliar problem is encountered. A singular, unchallenged

view of the world can lead down blind alleys.

When a team comprises mainly left-sided reasoners - those

who give priority to the logical, analytical, sequential, explicit and

verbal functions of the brain - overall performance is usually steady but

unspectacular.

These left-sided teams seem to reflect the style and approach

of senior managers within the regional structures of national contractors

during the 1960s and 70s.

In other teams there can be different reasoning processes

different views of the world and different starting points for solving

problems. Despite varying approaches to problem solving, the existence

of a reasonable level of compatibility ensures that the points of view

of others and their lines of reasoning will be understood and acknowledged.

Given this compatibility, there is usually a very open debate on basic

assumptions about the business, its problems and possible solutions.

These teams are often slow to start, spending time checking

assumptions and understanding the business from a variety of perspectives.

But this variety enables such teams to manage crises well. Generally they

are the high performers. But such performance is achieved only after it

has been recognised that managing individual differences and team-work

is as important as managing the business.

While some variety in approaches to problem solving in a team

can be very helpful, there is a level at which differences are so great

and compatibility so low that there exists no common understanding around

which a team can develop.

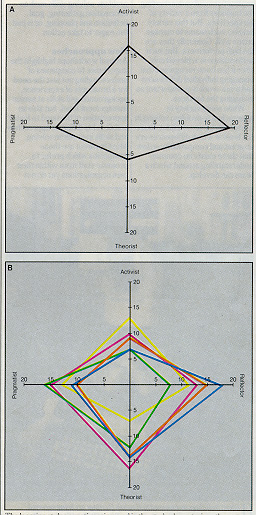

The learning styles questionnaire used in the study characterises the

individual in terms of four dimensions: activist, reflector, thand pragmatist.

The top diagram shows a subject who is a very strong reflector, who is

also a strong activist and moderate pragmatist, but a weak theorist. The

compatibility of a group can be judged by superimposing the individual

profiles of the members and interpreting the major similarities and differences.

The lower diagram shows an example of a group with low compatibility.

_____________________________________________

The approach to tackling a problem taken by one individual

can seem irrelevant, even irrational, to another. The way in which one

member wishes to manage the team may be diametrically opposed to that preferred

by another.

Such teams can absorb disproportionate amounts of time in

managing, or trying to manage, the process of team-work leaving little

energy for managing the business.

However, even these teams outperform another type of team,

that which either lacks problem-solving skills such as information gathering,

goal definition and planning, or is just too eager to take action.

New approaches

Arousal workshops highlight the importance to companies of understanding

not just the need for a broad mix of experience, backgrounds and skills

at senior management level, but also an appreciation of the need to foster

and develop different approaches and skills in problem solving. Most at

threat are those companies which prefer to promote staff from within their

own organisations yet do not have any planned means for broadening the

outlook or problem-solving skills of their staff.

Another implication is that individuals do not choose the

teams in which they have to work. Some teams gel immediately, while others

require greater conscious effort to function effectively.

Clearly it is important for individuals to be able to assess

their own strengths and weaknesses in team working and the skills of others.

But it is equally important that organisations provide their staff with

the insight and skills necessary for effective team building, as well as

for implementing organisational changes and instilling new values among

members of senior management.

Finally, there is a further need for companies to provide

their managers with opportunities to challenge existing practices and to

demonstrate an alternative approach to the problems that occur without

fear or prejudice.

Peter Lansley is a Reader in the Department of Construction Management, University of Reading; an associate member of faculty at Ashridge Management College; and visiting professor to the Construction Executive Program at Stanford University, California.

Scanned from Building, 27 June 1986